Before you see Arkansan Adam Riley and Canadian Matty Clarke set out to row 2,200 miles of the Northwest Passage in handmade boats in our new documentary, “Passage,” airing Thursday, Nov. 7 at 7 p.m., let’s dive into its history and the travelers who came before.

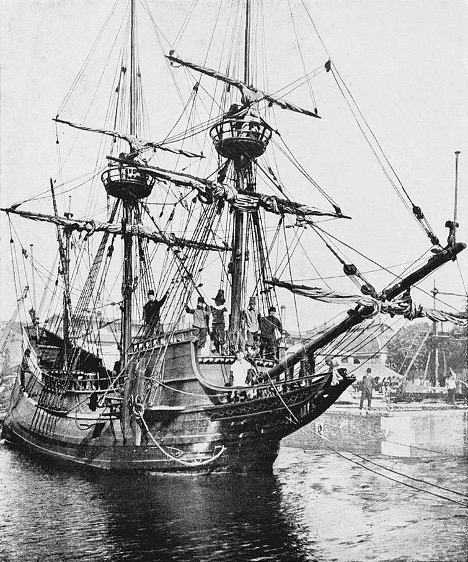

The Halve Maen, captained by Henry Hudson in the 1600s.

The First Age of the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is revered as one of the last great adventures on Earth. Originally referred to in 15th century myths as the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the passage is a treacherous and fickle sailing route connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans over northern Canada.

A minister in the court of Queen Elizabeth first used the phrase “Northwest Passage,” further describing the region as a “meta incognita,” or shore of uncertain worth.

It was this promise of wealth that spurred dozens of expeditions across the Atlantic between the late 15th and early 17th centuries. England deployed Henry Frobrisher in 1576, as well as Henry Hudson in 1607 and again in 1608. These expeditions mapped northeastern America – leading to the discovery of Baffin Island and the Hudson River Valley, respectively.

Hudson returned to Canada again in 1609 – this time sailing for the Dutch – however, after losing his way in the shifting ice of the Arctic, his men mutinied – leaving Hudson, his son and seven officers helpless. Their remains were never found.

Hudson’s tragedy would only be the first in the search for the passage.

The 18th century saw continued exploration. But, the early 1800s spelled war, as Napoleon sought to conquer Europe. By the end of the war in 1815, European navies were booming. Their massive ships sported steel-reinforced hulls and full libraries, while their ranks were bloated with ambitious young officers without hope of advancement or a war to fight.

The Second Age

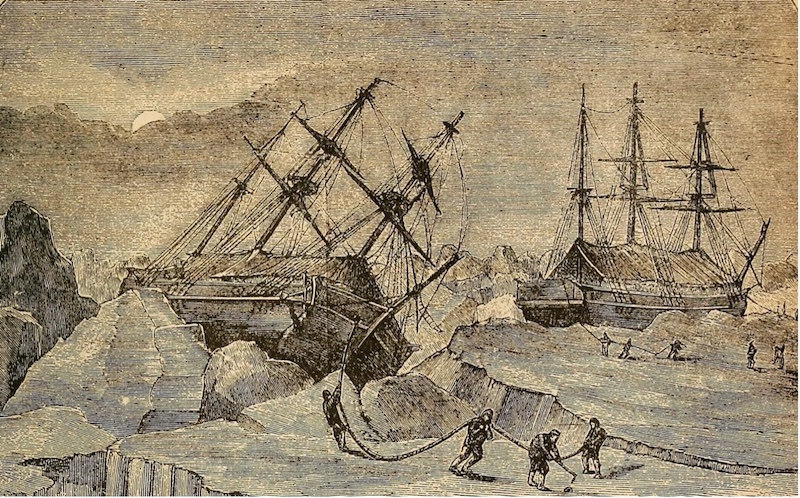

The HMS Erebus and HMS Terror trapped in ice in Victoria Strait during the doomed Northwest Passage expedition led by Sir John Franklin. From “The Frozen Zone and its Explorers” by Alexander Hyde, A.C. Baldwin, W.L. Gage, 1874

With the world at peace, England again turned to exploration and treasure seeking. In May of 1845, Sir John Franklin set sail for the passage with 24 officers and 110 men aboard two ships. Those ships – the Terror and Errebus – were former war vessels, steel hulls and all. Franklin and his men met with whalers in Baffin Bay (eastern Canada) and were warned of the shifting sea ice, which rendered the passage inconsistent and narrow. Franklin’s huge ships forged ahead.

The unyielding steel hulls inevitably got caught between the widening ice floes. Franklin and his men were never to be seen again. They simply vanished.

Regarded as possibly the greatest naval tragedy ever, the disappearance of Franklin motivated every captain in Europe to set out to find the Terror and Erebus – and discover the Northwest Passage along the way.

Over the remainder of the 19th century, more than 40 expeditions were deployed for the passage, including The HMS Intrepid and The Resolute – both of which had harrowing journeys of their own.

But, by 1900, no one had crossed the passage, and European states were losing funds and interest …

Welcome to the 20th Century

Gjoa frozen into the ice in Gjoa Haven. Winter 1904.

Norwegian Roald Amundsen had grown up hearing the adventure stories of Hudson and Franklin. His early journals show that he questioned the size of the warships the British had used as exploration vessels. He knew that “sailing small” would lead to more suffering, but he believed that suffering would lead to discovery.

In 1903, Amundsen put his money where his mouth was, setting sail aboard the Gjoa, a small vessel with a crew of only six men. The first leg of the journey was mostly unremarkable, and Amundsen and his men anchored in August of that year, off the eastern coast of King William Island in a small native village that would later be known as Gjoa Haven.

Amundsen and his men spent two winters living among the natives, before setting out westward again in August of 1905. By early 1906, Amundsen reached the Bering Strait and met a whaling vessel, which had departed San Francisco. It was then Amundsen knew he had completed a journey almost five centuries in the making.

HOW TO WATCH

Watch the journey of “Passage” on Arkansas PBS on Thursday, Nov. 7, at 7 p.m., or watch anytime on the PBS app.